Paul Polman: “The new normal calls for net positive companies”

Press release - On Wednesday 7 July an inspiring brainstorm took place at organic distributor Eosta, between Paul Polman, former CEO of Unilever, Volkert Engelsman from Eosta, Daan Wensing from IDH ─ The Sustainable Trade Initiative, and various journalists and professionals from the food sector. The mini conference (‘Pioneering the new normal’) was about the future of food and entrepreneurship in the post-corona era. The pandemic appears to have dramatically tipped the scales in favour of sustainability, but the obstacles are enormous. Courageous leadership, prototypes and True Cost transparency are all necessary to break through the barriers and achieve an economy of net positive companies. “I still believe in the fundamental goodness of people. This is a good moment in history to test it," said Polman.

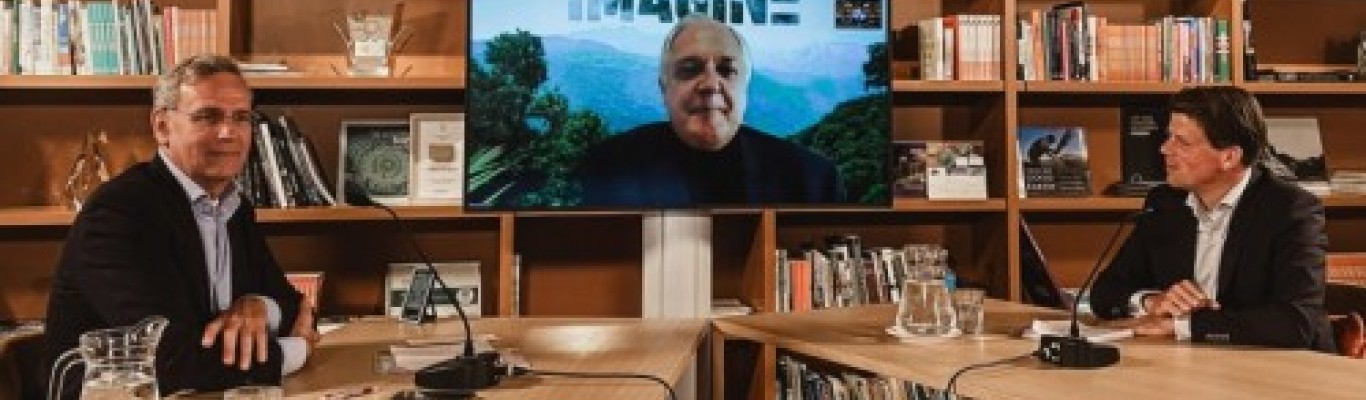

On Wednesday afternoon, a special mini conference for a live audience of 25 people and 103 online attendees took place at the offices of Eosta/Nature & More in Waddinxveen. Paul Polman set out his vision for the future of business. It was the same vision he relied on for ten years when steering Unilever against the tide of London’s shareholder capitalism: large companies must serve the future of humanity. This is the only way we as a society can cope with all ecological and social crises.

Volkert Engelsman, host and CEO of Eosta, summarised the challenge we’re facing: after the corona tidal wave, three much larger tsunamis are looming on the horizon: the far-reaching health crisis in which food plays a central role; international inequality; and the ecological crisis in which climate, biodiversity, water and the earth are inextricably linked. “As a company, you cannot continue to function in this world if we don’t make it fairer, more sustainable and more inclusive,” Polman summed up the essence of the challenge.

Tipping point: a widespread appeal

According to Polman, Engelsman and Wensing, the economic playing field has been tilting spectacularly since COVID-19. The organic sector has been crying out for a transformation of the food system and the economy for years, but now the appeal has become mainstream. Large companies with previously unshakeable power are being held legally accountable, such as in the case of the environmental group Milieudefensie versus Shell. The EU has prepared a Corporate Social Responsibility Directive that requires companies to report on their sustainability performance from 2023, and Germany has drafted a bill that imposes a social duty of care on companies. With its Green Deal and Farm to Fork strategy, the EU is striving for the radical greening of agriculture, with 25% organic farming and 50% less pesticide use by 2030.

The World Economic Forum is also pushing for a Great Reset in which human, social and environmental health become the economy’s top priorities. Popping up everywhere nowadays, this threefold vision of sustainability is fracturing the traditional view of the economy. It is even permeating the world of finance and major risk assessors, with central banks carrying out climate and biodiversity stress tests against large-scale investments.

Volkert Engelsman concluded: “It is clear that the short-term thinking of shareholders has had its day. As Feike Sijbesma put it: as a company you cannot be successful in a world that fails. We have to start working with a profit definition where people, society and the environment are all winners.”

Polman: "Covid-19 has shown that we can react very fast if the urgency is there. Can we use that to tackle climate change and the other sustainable development goals?"

From ‘less bad’ to ‘net positive’

Polman, who will publish a new book in October focusing on the concept of ‘net positive’, argued that companies must play a key role in the necessary economic transformation. Many companies are now trying to be ‘less bad’, but in the future ‘net positive’ must be the norm. Polman’s view is that this can only happen if CEOs of large companies realise they are not working for themselves or their shareholders, but for the future of humanity. A net positive company is a company with a positive operating result after the entire impact the business has on the environment and society has been taken into account (for example, with the help of True Cost Accounting). Such companies are extremely rare.

Net positive is possible

Polman complimented Eosta for being a company that is already net positive. Eosta, an organic distributor since 1990, is one of the first companies to have a True Cost Accounting analysis carried out (in 2017) in order to calculate its net impact. The tentative calculation by EY and SMI (for 2015) revealed a net positive result of more than 2 million euros for a turnover of approximately 100 million euros.

How does Eosta achieve this in an economic field that penalises sustainability? Eosta is a 100% organic company that, from its very beginning, has set itself an inclusive profit target, summarised in its mission statement ‘healthy, fair, organic’. The first thing that has made this possible is a closed corporate structure, so there is no interference from shareholders driven by short-term profit. Secondly, Eosta works with an integral sustainability model (the Sustainability Flower) to Manage, Measure, Market and Monetise the impact of production. This serves various sustainability goals: sustainability in cultivation, transparency towards the consumer (which empowers them), capitalisation of sustainable efforts for the growers, and an inclusive profit for society that can be calculated using True Cost Accounting.

Obstacles

Journalists from publications including Follow the Money, Trouw, Volkskrant and the German, English and Dutch trade press attended and asked some critical questions. It sounds virtuous, but how can it be achieved? Because the current economy has so many obstacles, as several of the speakers also pointed out.

Many large companies are stuck in the old normal because they are trapped by their own ‘stranded assets’. This applies not just to fossil fuel companies like Shell, but also to companies that have invested in intensive livestock farming, such as Rabobank or ABN AMRO. Or investments in processed food (“junk, not food”, as Engelsman puts it), which undermines instead of supports people’s health. It’s not just about companies either: governments that have put their fate in the hands of large companies are also up to their elbows in this.

The big obstacle for sustainable companies is that they are operating on an uneven playing field, in an economy that rewards externalisation. Purchasing in an ecologically and socially responsible way and paying a Living Wage costs money, which is at the expense of the profit and loss account that the banks use to judge companies. This affects all parts of a company. Journalist Jeroen Smit describes in his book ‘Het grote gevecht’ (‘The Great Fight’) how, during his time at Unilever, Paul Polman embodied the concept of sustainability to the outside world, but internally had to reward the marketeers and buyers on margin. Daan Wensing from IDH sees this as the biggest challenge on the path to achieving a Living Wage: how can companies work sustainably in an economy that punishes sustainability?

Courageous leadership

Various solutions were discussed during the seminar. Paul Polman emphasised the importance of courageous leadership. “What we need is CEOs with guts. We need pioneers who are willing to stick their necks out and prototype the new normal, even if they are currently operating on an uneven playing field where polluters have the competitive advantage. COVID-19 is a piercing appeal for courageous leadership.”

These CEOs also need to stand strong in the face of obscene incentives. As Jeroen Smit describes in ‘The Great Fight’, Polman himself was offered 200 million dollars by a Kraft Heinz director to participate in the takeover – Polman didn’t even entertain the proposal.

Prototypes needed

Wensing and Engelsman emphasised that the time is now ripe for business incubators and pioneers, both small-scale and large-scale: “We need prototypes, companies to come up with a ‘proof of concept’ for the new normal. During the coronavirus pandemic, we saw how consumers worldwide opted for more fruit, vegetables and organic food. The market is hungry for sustainable solutions that make sense, both ecologically and socially.”

Transparency as a bridge of awareness

Engelsman also pointed out the need to bridge the gap in awareness between visionary entrepreneurship and short-term shareholder interests: “Exploitation always rides on the back of anonymity. Only by ignoring the negative consequences of exploitation can you monetise externalisation in the market. That is why it is also called ‘external’ costs: they are thrown over the fence and made invisible. But we are now discovering that the other side of the fence is also actually our garden. One fence after another is disappearing. You have to do the opposite: create more transparency about the impact of your production on people, society and the planet. This is how you can bring awareness into the mechanics of the economy and arrive at a profit definition that is fair, inclusive and sustainable.”

Eosta, with Nature & More as its consumer brand and transparency system, is Europe’s most awarded distributor of organic fruit and vegetables. Eosta is known for its sustainability campaigns such as Living Wage, True Cost of Food and Dr. Goodfood. In 2018, the company won the King William I Plaque for Sustainable Entrepreneurship and in 2019 the European Business Award for the Environment. See also www.eosta.com and www.natureandmore.com.

END OF PRESS RELEASE

Contact and images:

Monique Mooij, Marketing Coordinator

E: monique.mooij@eosta.com

Marie-Ange Vaessen, Marketing Manager

E: marie-ange.vaessen@eosta.com

Telephone: +31 (0)180 63 55 500